One Saturday in September 2022, I was at home when our older son arrived back. He came straight up me, clearly unsettled, saying: ‘Mum, I read this article earlier….’.

I knew exactly the article he was talking about.

It was written by Guardian journalist Merope Mills, describing in unsparing detail the catalogue of medical mistakes that led to her daughter Martha’s death in 2021. The 13-year old died despite having a treatable condition; despite being in a hospital which had the expertise, time and resources to save her; despite numerous opportunities; and despite her parents repeatedly trying to tell doctors they thought their daughter was seriously unwell.

It was a raw and searing read. Enough to stop anyone in their tracks.

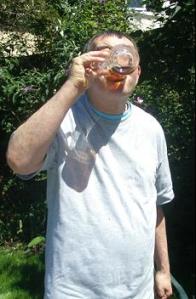

But for us, it was flooring. It took us right back to the fear and panic we’d felt nearly a decade earlier when medics responded to a previously healthy husband and father who had become unable to walk or speak, not with urgency but inaction and attempts at buck-passing.

Merope wrote that Martha died due to ‘complacency, overconfidence and the culture on the ward’ at the hospital where their daughter had been taken after an apparently minor injury on a family holiday. In a later article, her husband Paul Laity blamed ‘arrogance and office politics’ for the failure to move Martha to intensive care when there was still time to save her.

Merope described how their faith in the medics had turned to ashes: ‘We had such trust. We feel such fools.’

Reading about Merope and Paul’s unfathomable grief jolted us back into remembering how a mix of NHS turf wars and complacency meant our two sons came so so close to losing their dad.

‘Shout the ward down,’ is Merope’s advice now to anyone who thinks hospital treatment is going seriously wrong.

We knew exactly what she meant. A few months after my husband had been taken ill (and was by then making a good recovery), I wrote:

‘Sometimes you have to shout, literally, to be heard. Sometimes, you have to argue and demand and sob to get anyone to take any notice. Acting like a demented harpy is distressing and draining, but it may be what keeps the person you care about alive.’

Merope describes their attitude towards the doctors as ‘articulate, grateful and trusting’.

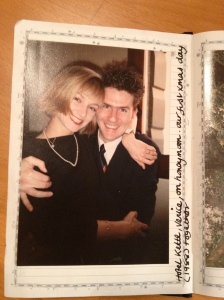

We also started out at the hospital that day believing the cavalry was on its way. Like Merope and Paul, we had been on a family holiday in the UK, when Tim started complaining of headaches, followed by vomiting, and then losing the ability to communicate. In a state of fear and bewilderment, we drove him to A&E on the Friday evening where, after a scan, he was admitted. We were told to come back early the next day.

The three of us sat hour after hour in the admittance ward on that Saturday, expecting the promised consultant would appear any moment: a plan would be formed; and we would be given even just a snippet of information to explain what was happening and allow us to get back on to solid ground.

I remember trusting that if we made ourselves quiet and small and biddable as we kept vigil by Tim’s bed, the system in its benificience would swing into action to protect us. Instead, our quiesence meant that we – and crucially Tim – were ignored by everyone other than the nurses who attended to him and tried to offer me sandwiches. What I hadn’t appreciated then was that our National Health Service may not be as national as you might think: because we were away from home when Tim was taken startlingly ill, the response of specialist hospitals asked to accept him as a patient was to try to pass the buck.

Of course, for all the parallels, the reason Merope’s article hit us so hard was precisely because, for the last 10 years, we have had the luxury of not dwelling on the events of July 2013. Unlike them, we have been able to forget. For all the similarities, in the only aspect that truly matters, there is no comparison between what happened to us and what happened to Merope and her family. Tim survived. Martha did not.

Ultimately, we were able to get the doctors’ attention and prompt them to act, while there was still – just – time to save him.

After probably the longest day of our lives, a junior doctor came to find us by Tim’s bed (the first doctor to speak to us since A&E). Finally, someone was going to take charge. Finally, everything would make sense.

Here’s the thing, she said: the specialist hospital 45-minutes away won’t take him; the specialist hospital close to our home five hours away will take him – but only if he arrives by air ambulance with an anaesthetist, as they say he’s too ill to travel that far by road. However, he can’t be taken by air ambulance because, as an adult man, he isn’t enough of a priority. ‘A baby might need the air ambulance,’ she explained.

The answer to this connundrum was to leave him in the admittance ward for the next five days, ‘and we’ll discuss his case at our next regular team meeting on Thursday’. (Today was Saturday.)

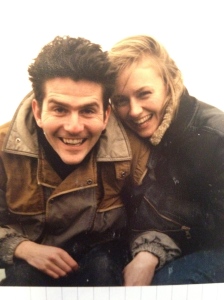

As my sleep-deprived, panic-addled brain struggled to unpick her words, our 15-year-old son – who had remained impassive all day, at one point calmly feeding his barely conscious dad soup from a spoon – crumpled to the floor.

OK, I thought. Even if Tim can survive five days of just waiting for something to happen, the three of us won’t.

All day, we’d clung to the (I am sure genuine) reassurances from nurses that their more senior colleagues were just working out the finer details of where and how they were going to move Tim for the specialist treatment he so obviously needed.

Instead of focusing on him and his family, the doctors had been arguing among themselves. Trying to shirk responsibility for his care.

At this point, what I can only describe as survival instinct kicked in. If my family was to emerge from this unfolding catastrophe, I would have to force the medics into action. I would need to marshall my thoughts and argue as I had never argued before. However hysterical and unhinged I felt, I had to stay calm and coherent enough to point out what seemed the obvious flaws in their plan (such as, how can Tim be too ill to be moved to London by road, but not ill enough to warrant an air ambulance for that journey? How does that make sense?)

All day, I’d been in contact with GP friends in London, who were as alarmed as we were that no doctor had been to see him. At 18.19, as the junior doctor went off to re-confer with colleagues, I texted them: ‘we r desperate and no one is doing anything….what can we do? cal and saul r in pieces. can we get private bulance? do such things exist?’

Our friends called minutes later. They had tracked down an anaesthetist colleague, and were getting quotes for a private air ambulance to move Tim. If no one else would save him, we would do it ourselves.

I never found out what an air ambulance would have cost. Nurse Cathy, who had waited with us long after her shift, came to find me. In what felt like a miraculous turn of events, a consultant had now agreed to come to the ward.

It was mid summer. We had been at the hospital since early morning, but it was dark outside when we were finally shooed out of the bay so the doctor could examine Tim. We were then called into an office. The local specialist hospital had had a chance of heart, the consultant informed us matter of factly, and would take Tim, after all. Some time after 10pm, Tim was put on a trolley and then driven there in an ambulance.

We didn’t know it then, but that move saved his life.

A day later, his condition – which had been wrongly diagnosed – massively deteriorated, and he was rushed into emergency surgery. The specialist hospital scrambled a world-class team of surgeons within minutes – with the head of department coming in from home on the Sunday to perform the operation. The speed at which they could act saved Tim’s life and we will be forever awed by their skill, dedication and clarity of purpose – every resource available was focused on keeping Tim alive. If he had been languishing on the admittance ward, as planned, attended by nurses only able to take his temperature and administer pain relief, we would have lost him.

This month (April 2024), Martha’s Rule comes into force at 100 hospitals across the UK. As the name suggests, it came about as a result of fearless campaigning by Martha’s family, and gives patients and their families the right to ask for a second opinion if they think something is going wrong. As Merope says: ‘I had no one to turn to.’ If her family could have insisted on a second opinion, the severity of Martha’s condition would have been spotted and her life saved, she believes.

Martha’s Rule means that rather than having ‘to shout the ward down’ or ‘act like a demented harpy’ to get attention, families will ‘know there’s a lever you can pull if things go wrong and no one is listening’.

In Tim’s case, the medics didn’t even pretend anything other than office politics was driving their decisions. However shocking, such blatancy at least had the effect of catapaulting us into action. We knew if he was going to survive, we would have to be our own cavalry. Next time, we might not be so lucky. Next time, they might try to fob us off by saying it was all under control when it wasn’t. Next time, pleading and persuading and making what seem really really good compelling points might still not be enough to be heard. Which is where Martha’s Rule will come in.

Merope wrote: You, or someone you love, will be in hospital at some point in your life. When that happens, you’ll need some patient power.’

When you listen to Merope speak in media interviews, you can hear in her voice the unrelenting anguish at the irreparable wrong done to her family by people whose literal job it was to save Martha. That will never leave her but Martha’s Rule could save hundreds of families from the same kind of avoidable shattering grief. It’s too trite to imagine that will bring more than a sliver of comfort, but the rest of us owe Merope, Paul and their family an immense debt of gratitude.

It has been years since I used to visit there multiple times a week. But for a long period, the only way I could get through the week was by spending time at her graveside (which mainly involved trying to keep her older brother from falling over in the ever-present mud). More than two decades on, we rarely go there now, but the place still has huge emotional pull. As my older son was about to go off to university, and I was dreading his going, it felt only fitting that the two of us make a pilgrimage to see his sister, and wander around some of the other graves. Reflecting on it now, I think it was a way for me to make his looming departure more manageable: a reminder that, however daunting the prospect of an empty (or part-empty) nest might be, it was a loss I could manage. Even though he would be away, he wouldn’t be gone.

It has been years since I used to visit there multiple times a week. But for a long period, the only way I could get through the week was by spending time at her graveside (which mainly involved trying to keep her older brother from falling over in the ever-present mud). More than two decades on, we rarely go there now, but the place still has huge emotional pull. As my older son was about to go off to university, and I was dreading his going, it felt only fitting that the two of us make a pilgrimage to see his sister, and wander around some of the other graves. Reflecting on it now, I think it was a way for me to make his looming departure more manageable: a reminder that, however daunting the prospect of an empty (or part-empty) nest might be, it was a loss I could manage. Even though he would be away, he wouldn’t be gone.

The Human Rights Act is equally poorly served by its friends. While defenders of the 1998 act bang on about Magna Carta, King John, the barons, Britain’s centuries old tradition of promoting international order, etc, etc, its opponents go for the jugular with stories of how it only protects terrorists and criminals (see left).

The Human Rights Act is equally poorly served by its friends. While defenders of the 1998 act bang on about Magna Carta, King John, the barons, Britain’s centuries old tradition of promoting international order, etc, etc, its opponents go for the jugular with stories of how it only protects terrorists and criminals (see left).